The fort package is useful when you need to either

perform random orthonormal transformations (i.e., random rotation

with/without a reflection) or random projections (particularly when it

is beneficial that the projections are uncorrelated).

Due to their use of fast structured transforms, these can be much

faster than performing the equivalent operations using matrix

multiplication. More specifically, fort transforms are

generally faster when working with spaces of dimensionality 64 or

larger.

This vignette exemplifies how to use the fort package,

in practice.

Basic usage

To use fort, you just need to use the

fort() function along with the usual matrix operations

(e.g., %*%, solve()):

library(fort)

# generate some random data (100 R^64 vectors)

my_matrix <- matrix(rnorm(100 * 64), nrow = 64)

# get a random orthonormal transformation from R^64 -> R^64

my_transform <- fort(64)

print(my_transform)

#> fort linear operation: R^64 -> [fft2] -> R^64

# apply the transform to the matrix

new_matrix <- my_transform %*% my_matrix

# verify isometry

# (compare Frobenius norm of matrix before/after transform)

sqrt(sum(my_matrix^2)) - sqrt(sum(new_matrix^2))

#> [1] 0

# invert transform

my_matrix_estimate <- solve(my_transform, new_matrix)

# verify inversion

# (Frobenius norm of difference should be small)

sqrt(sum(my_matrix - my_matrix_estimate)^2)

#> [1] 3.966255e-14

# get the transform in matrix format

my_transform_matrix <- as.matrix(my_transform)

fort for dimensionality reduction

One practical case in which fort can be useful is in

data-independent dimensionality reduction methods. In particular, it can

be used to implement an (approximately) orthogonal Johnson-Lindenstrauss

transform:

library(fort)

# generate high-dimensional sparse vectors

n_samples <- 1000

dim_input <- 2048

sparse_data <- matrix(as.numeric(rnorm(n_samples * dim_input) > 0), nrow = dim_input)

# we should be able to reduce the dimensionality of the space while mostly

# preserving distances

dim_output <- 128

sketching_transform <- fort(dim_input, # input dimensionality

dim_output, # output dimensionality

type = "fft2", # type of transform to use

seed = 42

) # seed for reproducibility

# reduce dimensionality of original sparse data using our transform

reduced_data <- sketching_transform %*% sparse_data

# compare dot products in both spaces

# (the second calculation should be faster)

system.time(sparse_inner <- t(sparse_data) %*% sparse_data)

#> user system elapsed

#> 1.37 0.01 1.49

system.time(reduced_inner <- t(reduced_data) %*% reduced_data)

#> user system elapsed

#> 0.10 0.00 0.09

# vectorize dot products

sparse_inner <- as.numeric(sparse_inner)

reduced_inner <- as.numeric(reduced_inner)

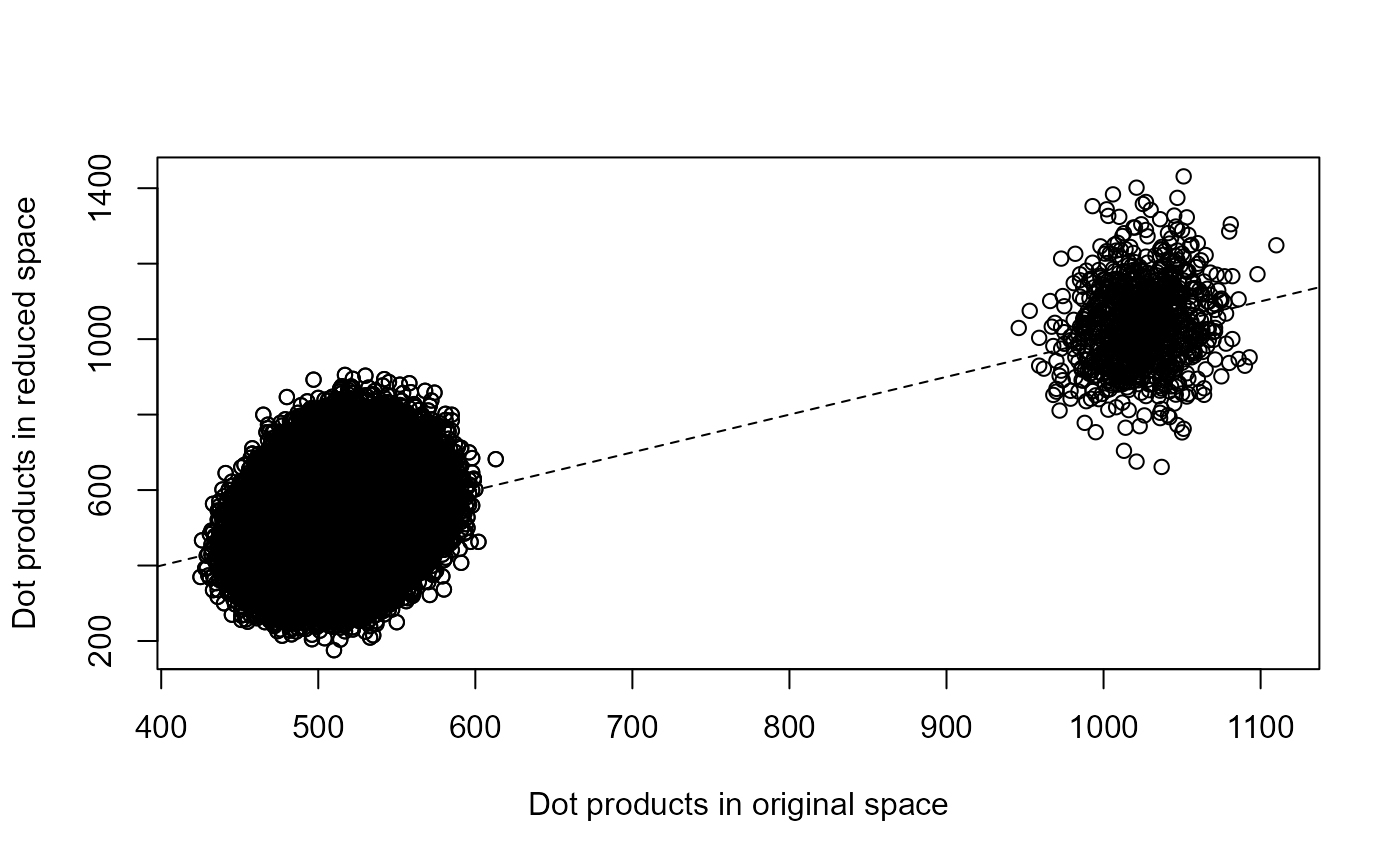

plot(reduced_inner ~ sparse_inner,

xlab = "Dot products in original space",

ylab = "Dot products in reduced space"

)

abline(0, 1, lty = 2)

# check relative errors

summary(abs(sparse_inner - reduced_inner) / sparse_inner)

#> Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

#> 0.0000001 0.0481897 0.1017553 0.1211966 0.1740701 0.7959228

# transpose matrices to comply with dist() convention

sparse_data <- t(sparse_data)

reduced_data <- t(reduced_data)

# compare distances in both spaces

# (the second calculation should be faster)

system.time(dist_original <- dist(sparse_data))

#> user system elapsed

#> 10.08 0.00 10.88

system.time(dist_reduced <- dist(reduced_data))

#> user system elapsed

#> 0.25 0.00 0.29

# vectorize distances and remove diagonal

dist_original_vec <- as.numeric(dist_original)[as.numeric(dist_original) > 0]

dist_reduced_vec <- as.numeric(dist_reduced)[as.numeric(dist_reduced) > 0]

# check relative errors

summary(abs(dist_original_vec - dist_reduced_vec) / dist_original_vec)

#> Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

#> 1.300e-07 1.940e-02 4.104e-02 4.864e-02 7.014e-02 3.024e-01Thus, this example illustrates that fort can be used for

fast and (approximately) isometric data-independent dimensionality

reduction, which can be used to accelerate algorithms that rely on

calculating distances or dot products between many high-dimensional

vectors, even when typical approaches (e.g., truncated singular value

decomposition) may be too expensive.

In this particular example, we see that fort can reduce

the dimensionality of the input vectors by 16 times (which results in a

dramatic speed-up when calculating dot products or distances), while

roughly preserving the distances between vectors (typical relative

embedding errors of about 5%).

fort for kernel approximation

Another practical use case for fort is in the stochastic

approximation of kernels via the “random kitchen sinks” approach.

For example, in the case of the angular kernel, it can be

approximated (in expectation) by the dot product in a space obtained by

projecting vectors along random directions and applying a

sign() non-linearity (i.e. \(\mathbb{E}(sign(w_i^T x)sign(w_i^T y)) =

kernel_{angular}(x,y)\) if \(w_i\) are drawn from an isotropic

distribution).

While the typical approach is to use random projections here (via

matrix multiplication), it has been shown that using random orthogonal

projections (such as the ones provided by fort) can reduce

the approximation bias.

To see this in practice, let’s compare the use of fort

vs. random projections in this context:

library(fort)

set.seed(1)

n_samples <- 3000

n_groups <- 4

dim_input <- 1024

noise_level <- 0.2

# assign samples to groups and embed them in N-dimensional space

data_group <- factor(round((n_groups - 1) * runif(n_samples)))

group_effects <- matrix(rnorm(dim_input * n_groups), nrow = dim_input)

noise_matrix <- matrix(rnorm(dim_input * n_samples), nrow = dim_input)

data_raw <- group_effects %*% t(model.matrix(~data_group))

data_raw <- data_raw + noise_level * noise_matrix

# calculate angular kernel using canonical approach

# first normalize vectors, to make it easier to calculate angular kernel

data_norm <- data_raw

for (i in 1:ncol(data_norm)) {

data_norm[, i] <- data_norm[, i] / norm(data_norm[, i], "2")

}

# the cosine kernel is the same as dot product when vectors are normalized

cosine_kernel <- crossprod(data_norm)

# clamp values to the [-1, 1] range

cosine_kernel <- matrix(pmax(pmin(1, cosine_kernel), -1), nrow = nrow(cosine_kernel))

# calculate angular kernel based on cosine kernel

angular_kernel <- 1 - 2 * acos(cosine_kernel) / pi

# get approximation of angular kernel using fort (with 2x expansion)

fort1 <- fort(dim_input)

fort2 <- fort(dim_input)

angular_expansion <- rbind(fort1 %*% data_raw, fort2 %*% data_raw)

angular_expansion <- sign(angular_expansion) / sqrt(dim_input * 2)

angular_kernel_fort <- crossprod(angular_expansion)

# estimate angular kernel using random projections (with 2x expansion)

random_matrix <- matrix(rnorm(2 * dim_input^2), ncol = dim_input)

angular_expansion <- random_matrix %*% data_raw

angular_expansion <- sign(angular_expansion) / sqrt(dim_input * 2)

angular_kernel_rndproj <- crossprod(angular_expansion)

# compare both approximations with true kernel

df <- data.frame(

true_kernel = as.numeric(angular_kernel),

approximated_kernel_fort = as.numeric(angular_kernel_fort),

approximated_kernel_rndproj = as.numeric(angular_kernel_rndproj)

)

cor(df)

#> true_kernel approximated_kernel_fort

#> true_kernel 1.0000000 0.9980077

#> approximated_kernel_fort 0.9980077 1.0000000

#> approximated_kernel_rndproj 0.9960411 0.9948214

#> approximated_kernel_rndproj

#> true_kernel 0.9960411

#> approximated_kernel_fort 0.9948214

#> approximated_kernel_rndproj 1.0000000In this case, we see that using random structured orthogonal

transforms (like the ones provided by fort) provides an

approximation of the angular kernel that is faster and more accurate

than one obtained using random projections.